The Mafia Flying In The Sky - Parasitic Birds

When we think of parasites, I think it's fair to say that worms and insect larvae typically come to mind. Most of us will have seen some variation of an invertebrate laying its eggs inside a host species, just for them to take control over and devour them from their insides (look up 'caterpillar eaten alive by wasps' on Youtube if you haven't seen one; it's quite elucidating). These are usually categorised into two groups: ectoparasites (e.g. ticks), which live on the outside of their host; and endoparasites (e.g. tapeworms or cholera bacteria), which live inside their host's tissues and organs. All ecto- and endoparasites are invertebrates or unicellular. Before, I would have also thought these to be the only parasites in existence - but there are exceptions to the pattern.

A couple of weeks ago while browsing Twitter feeds, I encountered an interesting comment that told of a certain species of bird - the brown-headed cowbird (Molothrus ater) - taking advantage of other birds to lay eggs in their nests. I hadn't heard of this behaviour in avians before, so I asked the person who posted the comment about it. They gave me some clues to start my own research, and so I was introduced to parasitic birds.

The Symbiotic Trifecta

Biologically, the term 'symbiosis' is defined as any relationship in which two or more species live closely together. Unlike the common interpretation of the word, this does not necessarily mean that both species will benefit from the circumstance. In reality, a symbiotic relationship can actually be classified into three subgroups, which include:

- Mutualism, where both organisms benefit from their interaction, e.g. legumes trading nutrients with nitrifying bacteria in the soil (which I spoke of in a previous post);

- Commensalism, where only one species gains from the relationship, with the other remaining unaffected, e.g. when cattle egrets feed on the bugs that are stirred up by grazing cows;

- Parasitism, where one species thrives from deriving resources at another's expense, e.g. fleas living and reproducing on a dog for shelter, to the dog's annoyance.

Symbiosis exists in all ecosystems on Earth, becoming increasingly more common in places with greater levels of biodiversity. This occurs as different species evolve over time to adapt to their environment and neighbours, gaining ways to work with/against each other more efficiently to have the best shot at survival and reproduction (a.k.a. natural selection). It should come as no surprise that rainforests and coral reefs are rich with symbiotic relationships, involving essentially all members of their respective habitats to form ecosystems unique to them. And once you start considering ecological niches - which are the roles that each species takes up in their habitat, including what they eat and which species eat them - then you can imagine just how intricate these connections can become.

In the case of birds, most species benefit from a commensal relationship wih trees; a robin might build a nest on an oak's branches, for instance. Such is the case with birds all around the world, from Canada to Africa to Russia. Hiding between the hundreds of avian species that do this, however, exists a specialised collection of renegades that play a different game from the rest. These are canny crooks intent on deceit and intimidation for their own needs, and they are probably the closest thing to a mafia in the animal kingdom. Enter: the cuckoo bird.

Brood Parasitism

Cuckoos are moderately sized birds in the family cuclidae, which are known to inhabit pretty much every livable continent on the planet. They also show the most diverse range of breeding strategies in a single bird family, raising their young by different means of parental care - and by interspecific brood parasitism, which has apparently evolved independently in 7 avian families (from hundreds) around the world. Take the common cuckoo (Cuculus canorus), native to boreal Europe. When viewed from afar, the large wings on the common cuckoo can make it look similar to a predator, such as a sparrowhawk or a falcon. Smaller birds, like the reed warbler (Acrocephalus scirpaceus), may become frightened by the sight and fly away from their nest, leaving it unguarded and a perfect target for female common cuckoos to lay their eggs on.

Once they've laid their eggs, common cuckoos leave the vicinity and essentially abandon them for the host bird to take care of, sparing the energy required to rear offspring for other tasks (like reproducing again, thereby resulting in greater fecundity). The question here is whether the host bird can identify the additional egg in her nest once she's back. Alas, many brood parasites (including the common cuckoo) have evolved to parasitise on only small ranges of bird species, and so the way their eggs look have evolved with them. This means that, over time, their eggs appear more similar to host-eggs - leading to the phenomenon being known as egg mimicry.

Though egg mimicry does not often result in parasite-eggs becoming completely identical to host-eggs, it generally does a good enough job at fooling host parents to accept them. Many brood parasites have also developed a variety of complementary little tricks to swindle the deal in their favour, such as minimised hatching times, which allow parasite hatchlings to eject host-eggs from the nest before host-chicks are born. Such hatchlings are usually larger and more competitive than the host species, so even live host-chicks may end up malnourished (as the parasite keeps taking the food from mama-bird) or just outright slaughtered before they can defend themselves. Either way, the parasite procures the nest's resources for itself.

Clearly, it is in the host species' favour to prevent this from happening. As such, some have evolved to have improved sensory organs for distinguishing parasite-eggs and hatchlings apart and larger beaks for their subsequent removal. These adaptations become selective pressures for the brood parasite, making it evolve to lessen the chance of egg rejection, thereby prompting the host species to also evolve, and so the interaction escalates. This parasite-host coevolution is exhibited more distinctly as the two species become more interdependent over time, which has been observed to occur less with generalist species like the brown-headed cowbird - a brood parasite found in North America that targets a wide spectrum of unsuspecting passerine hosts in the area.

Interestingly, ornithologists have found that some host species accept parasite-eggs even when they should be able to identify them. Two arguments are usually proposed to explain this difference in trends, with the first known as the evolutionary lag hypothesis. This theory posits that accepting parasite-eggs happens simply because the host species has not yet evolved ways to deal with them, and that failed brood parasitism comes from the parasite species not having evolved mechanisms for overtaking the host's defences. Acceptance of nonmimetic eggs, as well as the high tax on hosts of being parasitised without apparent defence mechanisms, both support the theory. Since it is rather difficult to prove experimentally, however, this explanation often falls short.

The second argument is known as the evolutionary equilibrium hypothesis, and it is widely well-credited. It assumes that, when improved egg mimicry makes it difficult for a parent bird to identify the parasite-egg in her nest, the cost of egg rejection due to misrecognition and mistakenly damaging her own eggs makes simply accepting the parasite preferable. This is especially true with brown-headed cowbirds in North America; when a host bird rejects a cowbird's egg from her nest, the cowbird notices and flies back to the nest when the host parent is away to destroys her eggs in retaliation. I understand that nature can be cruel and all, but that's got to be the most vile, spiteful thing I've heard an avian do - similar to operating a mafia!

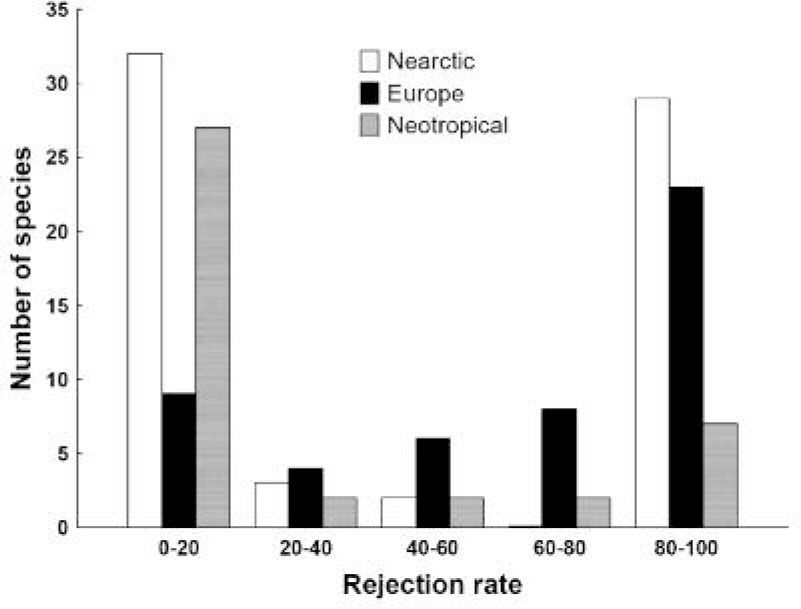

It becomes even worse when you realise how effective the cowbird's strategy actually is. According to a study from 2015, more host birds in the Americas (where the cowbird lives) accept parasite-eggs than reject them - an adaptive trait that limits the risk on the host-eggs. In comparison, most birds in Eurasia have evolved to counter brood parasitism, with the same study stating that the majority of hosts in the area recognize and reject parasite-eggs over 80 percent of the time.

Fortunately, some species are able to tackle their situation without needing to explicitly reject their parasite infiltrators. The cedar waxwing (Bombycilla cedrorum), for example, feeds its young a diet that consists entirely out of fruit, which is far too acidic for a cowbird hatchling to consume - so it dies. Still, brood parasitism has quickly proven to be a danger to a number of birds in the west. What do we do, then?

Impacts On Conservation

Over the past decade, trends seen in neartic and neotropical countries have indicated an increase in local exctinctions and a decline in biodiversity due to mass parasitism. This is happening today. Amongst the endangered species are Kirtland warblers, southwestern willow flycatchers and some types of vireos, with many more at risk due to the loss of habitats from deforestation and other human activities. In turn, conservation biologists argue that immediate action to directly manage and control parasite and host populations is critical for their continued survival.

So, hopefully you can see how important maintaining a balanced ecosystem is for its individual members. Though this is not meant to scare you, it should give you some food for thought - especially if you ever see a cuckoo bird flying around again.

References

- Croston, R. & Hauber, M. E. (2010). The Ecology of Avian Brood Parasitism. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/the-ecology-of-avian-brood-parasitism-14724491/

- Krüger, O. & Davies, N. B. (2002). The evolution of cuckoo parasitism: a comparative analysis. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1690908/

- Soler, M. (2015). Brood Parasite-Host Coevolution in America Versus Europe: Egg Rejection in Large-Sized Host Species. Retrieved from https://bioone.org/journals/ardeola/volume-63/issue-1/arla.63.1.2016.rp2/Brood-Parasite-Host-Coevolution-in-America-Versus-Europe--Egg/10.13157/arla.63.1.2016.rp2.full?tab=ArticleLink

- Hoover, J. P. & Robinson, S. K. (2007). Retaliatory mafia behavior by a parasitic cowbird favors host acceptance of parasitic eggs. Retrieved from https://www.pnas.org/content/104/11/4479

- Robert, M. & Sorci, G. (2001). The evolution of obligate interspecific brood parasitism in birds. Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/beheco/article/12/2/128/239797

- Rothstein, S. I. (1976). Cowbird Parasitism of the Cedar Waxwing and Its Evolutionary Implications. The Auk, vol. 93, no. 3, American Ornithological Society, 1976, pp. 498–509. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4084951